"The seeds of a different world are already alive": an interview with Georgie Sanchez

A new exhibit at Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York reminds us to take trans and queer art into the streets. I interviewed the co-curator Georgie Sánchez about it.

Installation view of ficciones patógenas. Photograph by Daniel Terna. © 2025 Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York.

Tavia Nyong’o: I’m here with Georgie Sánchez, artist, writer and curator, on Saturday, April 26, at Le Botaniste near the Leslie Lohman Museum, to unpack the coloniality of being—together. Georgie, can you start by telling me how you came to curate this exhibition?

Georgie Sanchez: The exhibition (co-curated with Stamatina Gregory, Head Curator on view through July 27, 2025) grew out of a group of people coming together to ask: How have mechanisms of deceit, theft, warfare/genocide, and disease become institutionalized over time in this killing machine we call America? The artists of Ficciones Patógenas, (pathogenic fictions), engage and refuse the grammars of dispossession in our current imposed binary existence. In their 2018 book, Ficciones Patógenas, which inspired the title of the show, Guaxu trans writer, activist, and participating artist Duen Neka’hen Sacchi traces their own medical history through Western regimes of bodily conformity. The wounding and suturing of Neka’hen’s body (and other nonconforming bodies), based on false notions of order and reproduction, echoes the violent reshaping of the “Indies,” which inextricably bound biology to nationhood.

The idea was to link present-day phenomena like evictions with legacies like post-1492 epidemics—not just as historical facts but as rubrics of ongoing colonial violence: genocide, lies, and sickness brought by colonizers.

Tavia: And from your personal perspective, what brought you to address these questions through art?

Georgie: I wasn’t trained in art history initially (although I’m now doing a PhD in Art History)—I came into this through the Mellon-funded project Dispossession in the Americas, as an arts administrator and curator. I was tasked with finding the artists and curators who could respond to these themes. Some of the curators also became exhibiting artists. The idea wasn’t just curatorial—it was political, even militantly so in some cases. Like for example the exhibition Nakoada in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil organized Denilson Baniwa. Baniwa is the first Indigenous guest curator at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio, who opened his tenure with an exhibition titled Nakoada, a word used by Baniwa people to mean war strategies of survival and permanence.

Tavia: How many countries did you visit while researching the exhibition?

Georgie: If we count Puerto Rico, it would be about nine: Puerto Rico, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Chile, Argentina, Brazil.

Tavia: Your curatorial approach reminds me of the Encuentros from the early 2000s that Diana Taylor organized out of NYU Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Did those gatherings influence this work?

Georgie: Absolutely. For example, the Mexico City project was titled inSURecciones: reflexiones en torno performatividades decoloniales (Insurrections and reflections on decolonial performativities) which was curated by Gabriel Yepez. Artists like María José Galindo, Carlos Martiel, Martha Hincapié Charry, and Lukas Avendaño were part of it. They weren’t just performing identity but rethinking hemispheric geographies—centering Aymara, Mapuche, or Afro-descended epistemologies rather than reproducing state-centric or traditional ‘latinidad’ narratives.

Tavia: So how does it feel to bring this show to the U.S., at a time when the very terms you use—“trans,” “and Latinx,”—are under attack?

Georgie: Sylvia Wynter once said, “Black Studies was a war.” That war hasn’t ended. I worried the exhibition would be read as tokenizing or assimilationist, which it’s not. No major outlet has covered the show [Since we talked, The NY Times gave it a weekend mention]. Not one. Yet 200+ queer and trans people came for the opening. Spontaneous solidarities emerged, even as the mainstream ignored us. And yes, New York is very different now—even from a few months ago. The chilling effects are real.

Tavia: That absence of press coverage seems part of a broader climate of fear. Even hosting gatherings feels fraught. But I wonder—given the themes of war, deceit, and disease—what does this exhibition offer in terms of queer and trans survival?

Georgie: Cultural theorist and visiting professor here at Princeton, C. Riley Snorton, has said that “To occupy the interstitial, to be the missing word, might be like finding oneself in the breach between the subject of enunciation and the enunciated subject or sitting on the razor’s edge where history and myth meet.” Each of the artists in this show presents different horizons of possibilities, missing or undetectable words, different ways of seeing, feeling, and knowing. Their creative practices reverberate Frantz Fanon’s unruly words that “one cannot divorce the combat for culture from the people’s struggle for liberation.” Writer, activist, and Lesbian Avenger, Sarah Shulman, ([who came to the opening of the exhibition!), has spoken forcefully about how to be a successful writer in a corrupt society — and I know she also means a cultural worker in a corrupt society. She writes that:

"We are living right now in a very sick society, one that is currently in the throes of a national cataclysm, and so— among the other twisted logics of white supremacy, male power, and violent nationalism— we also have this constant false messaging that repetition of what is already known is good writing, and that familiarity equals quality, when, in fact, it is the other way around: the most culturally valuable work is the one that invites us to question ourselves, how we think, and to vigorously question how we live.”

The artists of Ficciones Patógenas, among many things, do just that, they invite us to question ourselves and how we live today. Carlos Martiel told me once, “I’ve eaten injustice for breakfast.” That’s what this show is about—vernacular struggle, not abstract theory. Letting the artists speak the missing words.

Carlos Martiel, Lazos de Sangre (Bloodline), 2022, Courtesy of the artist.

Tavia: You also mentioned you didn’t want to frame these artists as “emerging”—some are long established, some have passed away, and for many this is their first New York show. Why the Leslie-Lohman Museum?

Georgie: Leslie-Lohman operates as a community art space. It felt right. We originally envisioned it as a collaboration with El Museo del Barrio, but they passed. That said a lot. This show needed a space grounded in queer, trans, and BIPOC collectivity. Medium-wise, too—there’s only one painting. The rest includes textiles, performance documentation, and works that blur genre. For example, artworks by Duen Neka'hen Sacchi, Mag de Santo, Lizette Nin, Lucia Egaña, and Seba Calfuqueo refuse both biological essentialism and nationhood.

Río Paraná (Duen Neka'hen Sacchi, Mag de Santo), Mil Sucesos perdidos hasta ahora [still], 2021. Digital video, color, sound, dimensions variable. Runtime: 41 min. 25 sec. © Rio Paraná (Duen Neka'hen Sacchi, Mag de Santo).

Tavia: One work that stood out to me was The Stone Butch piece, which calls to mind magical thinking in queer communities—tarot, crystals, astrology—but also links to extractivism, which I know you mentioned the artist is critical of.

Installation view of ficciones patógenas, curated by Georgie Sánchez and Stamatina Gregory, Head Curator / Director of Exhibitions and Collections (Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, March 14 - July 27, 2025). Photograph by Daniel Terna. © 2025 Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York.

Georgie: Yes. That work by Lucia Egaña and Ju Salguero critiques extractivism while referencing Jack Halberstam’s famous line about the “stone butch” being defined by what she does not do. It questions the commodification of identity, insists on re-enchantment of matter, and challenges us to see gender, sex and resources as connected sites of dispossession.

Tavia: And fiction itself—fabulation—is central here. To what extent is fiction necessary because truth-telling is dangerous?

Georgie: Deeply necessary. We’re living through epistemicides. Think of how oral traditions get erased. Myth and fabulation are survival strategies, especially for people whose existence is being targeted. That’s why artists like Neka’hen both embody and refuse “ficciones patógenas”—to fabulate against regimes of truth and verification that deny their being.

Tavia: Some of these ideas were incubated at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA) in Barcelona during Paul B. Preciado’s programming, is that right?

Georgie: Yes. Neka'hen attended Preciado’s seminars there. The MACBA museum has been a gentrifying force, but Preciado reframed the body as an archive, drawing on pharmacopornographic theory. For Neka’hen, the figure of the “Adam’s apple”—which they had surgically removed in childhood—became a site of epistemological inquiry. “What if Adam's apple was the apple you needed to eat to become a tree?” That’s the kind of epistemological reversal and the kind of artistic work they're engaged in.

Tavia: We’re living through the collapse of the old world order. What kind of futures do you think this project makes possible?

Javi Vargas Sotomayor, Huayco Epidemia (Constelación Chuquichinchay) (Huayco Epidemic (Chuquichinchay Constellation)), 2017, courtesy of the artist.

Georgie: Scholar JT Roane said in an interview that “the seeds of a different world are already alive in the everyday practices of ordinary Black and Indigenous people.” I believe that. I also believe in collectivity, not individualism. This exhibition centers networks of friendship and care—love, really—that transcend geography. They are artists staying in touch with each other across borders, surviving, imagining. Not just theorizing but taking it to the street. That’s where the last image in the show comes from—a protest banner. We always have to return to the street.

Installation view of ficciones patógenas, curated by Georgie Sánchez and Stamatina Gregory, Head Curator / Director of Exhibitions and Collections (Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, March 14 - July 27, 2025). Photograph by Daniel Terna. © 2025 Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York.

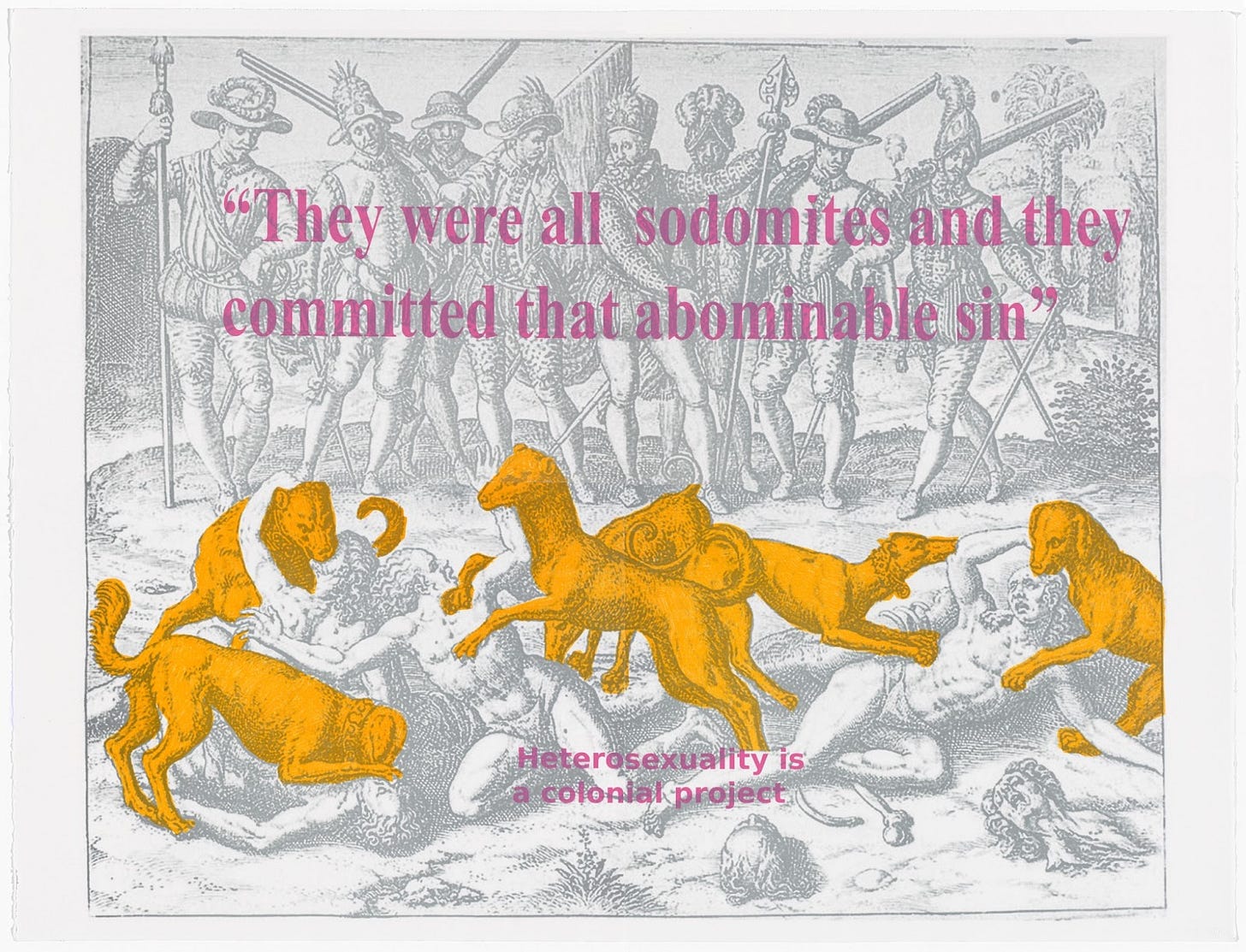

Colectivo Ayllu (álex aguirre sánchez, iki yos piña narváez, kimy/leticia rojas miranda, lucrecia masson córdoba, francisco godoy vega) Perrear el dolor (Perrear the Pain), 2020, Lithograph, Courtesy of the artists.